Beyond Fridges and Landfills: Shaking Up the Food Waste Debate

In villages worldwide, small-scale farmers drive seeds into soil every planting season with hopes for a successful harvest.

Tilling their fields, many pray for rain to reap the fruits of a bumper crop: Paying for their kids to go to school; buying livestock to increase their income; and filling their tables with nutritious food.

For Jane Bayitanunga, a mother of six in Uganda, her crops faced a different challenge three years ago.

“The rains came. But after the harvest, so did the weevils and the rats. We took a lot of caution, harvesting our grain using baskets and tarps to maintain the quality,” she said. “But it was all a waste of time. When we got home, we had no good place to store it.”

Sophia Namugaya lives a few miles away from Jane. Last year, she harvested 3,000 kilos of corn and lost 80 percent of it to rats, contamination and infestation.

Like other farmers in her village, Jane lost a good portion of her corn and beans. For every five bags she stored, one or two were ruined within a month — either damaged or eaten. In just months, some farmers lost up to 60 percent of their harvests, plagued by insects and mold.

This food loss is a cruel irony when more than 50 percent of the world’s hungry are small-scale farmers. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated in 2011 that annual post-harvest losses in Sub-Saharan Africa exceeded 30 percent of total food production. The cost came to $4 billion a year, surpassing what the region was receiving in foreign aid.

Since then, a large-scale effort to curb food loss and waste has been thrust on the global stage in the fight to end hunger.

Eat or Be Eaten

Approximately $1 trillion of food is lost or wasted every year — accounting for roughly one-third of the world’s food. According to FAO, reversing this trend would preserve enough food to feed 2 billion people — more than twice the number of undernourished people across the globe.

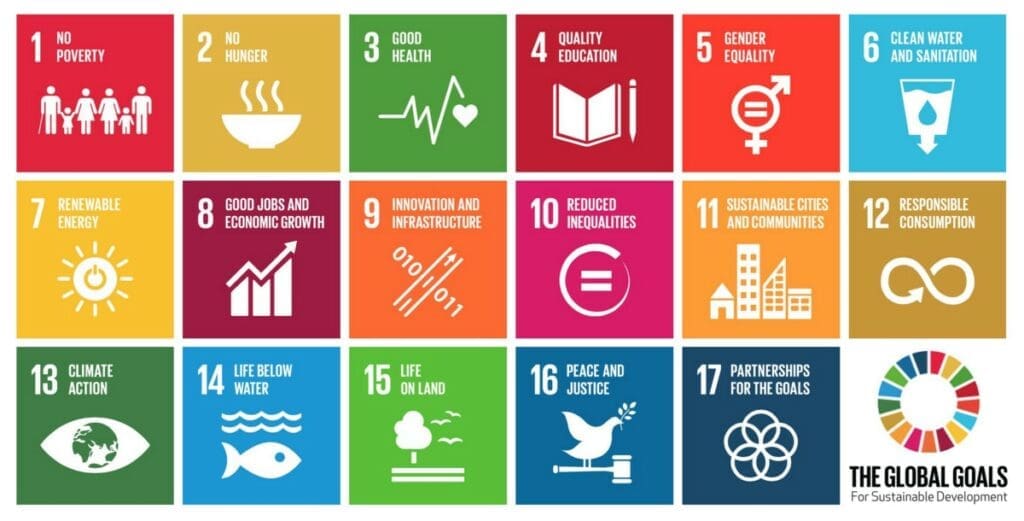

This potential has put the issue high on the global development agenda. At a time when 1 in 9 people go to bed hungry every day, the United Nations has challenged the world to cut global food waste in half by 2030 as part of its 17 sustainable development goals.

One of 17 global sustainable development goals adopted by the United Nations, goal 12 aspires to halve global food waste and food losses by 2030. (©globalgoals.com)

As one of the planet’s largest food producers and consumers, America’s overflowing landfills and fridges have become a powerful backdrop in the food waste debate. From what Americans buy in stores to what they dispose of in garbage bins, there is growing public consciousness about the global repercussions of what happens to our food once it reaches shelves and consumers.

But the world’s conception of food waste has expanded to include what happens to food long before it reaches our local grocers. And Jane’s tale and others like hers have inspired another global plan of action: Reducing food loss along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses.

Food loss can happen at every stage of the journey from farm to market. When food is handled, processed, stored and transported, there exists some risk of damage, spoilage or loss. Reducing food loss and waste has even inspired the adoption of a new Food Loss and Waste Standard to help businesses, governments and other groups measure what falls through the cracks.

Last fall, UPS’ humanitarian supply chain director Esther Ndichu argued that hunger isn’t actually a food issue — it’s a logistics problem that fails to effectively connect food with the people who need it most.

“Some of it rots in warehouses awaiting transport to the market, while some of it rots at ports and border crossings awaiting customs clearance,” Ndichu said. “And then some of it just rots in the fields because farmers do not think it’s economically worth it for them to harvest it.”

Esther Ndichu: Hunger isn’t a food issue. It’s a logistics issue.

Post-harvest losses, which make up most of the food loss in the world, are so devastating because many farmers already struggle to put food on the table. Losing 20 to 40 percent of one harvest like Jane did exacerbates food insecurity, and when families eat damaged crops, that can negatively impact their nutrition and health. Women understand this issue intimately because they often are in charge of drying, cleaning, and storing food.

These dynamics have put food loss front and center on the agenda of the World Food Programme (WFP) as it works toward a future without hunger — a future in which farmers like Jane have the tools they need to protect the food they grow.

3 Innovations in Food Loss Reduction

Earlier this summer, WFP launched its first-ever Innovation Accelerator. Its goal is to speed up progress in the fight to end hunger — and scaling advancements in food loss reduction is one of its many promising projects.

The Zero Post-Harvest Losses project sells low-cost, locally produced grain silos to farmers and provides them with training on post-harvest crop management. To date, the project has sold 65,000 metallic storage silos in Uganda alone, and smallholder farmers have learned up-to-date handling techniques from WFP and local farming organizations in five key areas: Harvesting, drying, threshing, solarization and on-farm storage.

The decision to scale the project was made after pilot initiatives in Uganda and Burkina Faso showed remarkable results. According to a 2014 WFP report, these interventions among 400 farmers resulted in a 98 percent decrease in food loss over a 9-month period. The project, supported by private sector partner UPS, was expanded to include more than 16,000 families later that year.

Small-scale farmers in Burundi using grain silos for storage.

The complementary benefits were significant. Farmers could effectively store their crops and sell them when market prices were higher; families experienced increased nutrition and reduced exposure to food contamination; and women’s workloads were reduced as the long process of daily cleaning and shelling of cereals was eliminated.

“The near eradication of post-harvest food losses at the farm level was a very significant outcome,” the report said.

Across the globe, a second innovation is empowering farmers with a new way to test and promote the quality of their crops.

Created in Guatemala in response to poisonous aflatoxins found on local harvests, the “Blue Box” serves as a testing kit for on-the-spot screening of food quality in the field. When used in tandem with trainings on post-harvest crop management with smallholder farmers, these joint efforts reduce the likelihood of food contamination and loss in farming villages around the world.

The Blue Box also supports two other important goals: By helping farmers improve crop quality, it’s less likely that families will suffer the negative nutritional consequences of eating low-quality food. It also helps crops meet quality standards for bulk purchase through WFP’s Purchase for Progress initiative, which buys high-quality crops from smallholder farmers to supply the agency’s food assistance programs, such as school meals.

A third innovation highlights why connecting rural farmers to viable markets remains a top priority. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, WFP has provided cargo bikes to mostly female farmers to increase their access to markets.

In the past, many women carried heavy sacks weighing over 100 pounds to deliver their produce to market. Now, they use cargo bikes to transport more of their surplus crops to sell in local markets. Sales of staple crops enable these women to buy the additional food they need to meet their dietary needs, including tomatoes, carrots, and fruits.

“By focusing on solutions, we can get food to the people who need it,” said UPS’ Ndichu. “Success depends on public and private partnerships bringing together governments, nongovernmental organizations and the private sector to invest in supply chains. If that happens, we can conquer hunger in our lifetime.”

One More Line of Defense

Back in Uganda, Jane’s fortunes have turned. Today, vermin and pests are no longer pilfering her corn and beans.

As one of 16,000 families to participate in WFP’s post-harvest loss expansion program in August 2014, she gained access to storage silos and information about the best time to harvest her crops, how to avoid pest attacks, and how to ensure they are free of insects before storage.

A woman in Uganda prepares school meals from the beans stored in a silo.

“We are extremely happy that these silos have been introduced to us,” Jane said. “They reduce infestation and contamination, they help us keep everything that we grow and allow us to store it for as long as we want. Besides the silos themselves, we have acquired a useful new skill as we now know how to dry our grain before it can be stored well in the silos.”

For smallholder farmers like Jane, these tools and knowledge serve as one more line of defense against hunger in an unpredictable farming environment.

As above-average temperatures and erratic rains spark droughts from Central America to southern Africa, and as conflict worsens food crises from Nigeria to South Sudan, the effort to curb food loss and waste may bring not just short-term prosperity for farmers like Jane, but long-term prosperity for the world.