School Health and Nutrition: Invest Now to Build Human Capital, or Pay More Later

By Mohamed Abdiweli Ahmed, WFP Advocacy Adviser

Sareeyo is a Somali mother of three — including two boys who have lost their father. For her, the meals her children receive at school are a godsend.

“I cried for happiness when I saw the children coming home satisfied with full stomachs,” she says.

Like her, millions of poor and vulnerable parents around the world find comfort in knowing their children’s health and nutritional needs are taken care of at school, and they benefit economically by not having to worry about one of the day’s meals. Like every country in the world, Somalia can only benefit from a healthy and educated youth population, and this is what school-based health and nutrition services build up to.

School feeding is part of a package of school health and nutrition services –which can include school feeding, vitamin and mineral supplementation, water and sanitation, deworming, vaccination, vision screening, malaria control, menstrual hygiene management and oral health — that not only provides children with the calories to fuel their learning but also gives parents (who might otherwise insist that their children– particularly girls — stay at home) strong incentive to send their kids back to school.

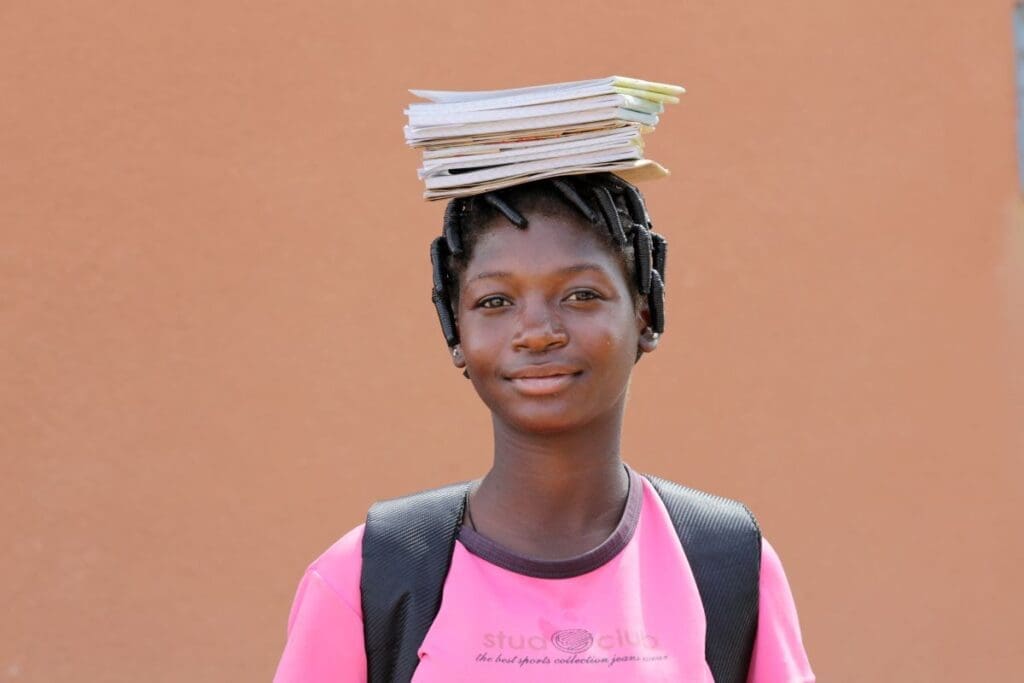

Girls are particularly at risk of dropping out of school, but school meals can be an incentive to stay.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Children

Tragically, for millions of children across the globe, COVID-19-induced school closures have disrupted critical education, health, nutrition and protection services delivered in and through schools. At the peak of the school closure crisis, some 1.6 billion students were unable to attend classes and 370 million children had missed out on school meals. For millions of these children, a lack of daily school meals has resulted in increased hunger, with a negative impact on their health and nutritional status. Sareeyo and her family bear witness to this:

“When I heard schools were closed for 15 days, we started suffering again, because I could not afford to feed my children twice a day and they felt hungry,” she says.

The pandemic’s disruption of education and other social services has affected the individual lives of these students as well as their learning and development, including their immediate health and nutritional needs. Meanwhile, the cumulative effect of this disruption on millions of pupils is affecting the development of human capital, especially in fragile and conflict-affected contexts where, typically, there is a lower starting point due to sustained periods of disinvestment.

At the peak of the coronavirus pandemic, some 1.6 billion children were out of school and 370 million had missed out on school meals.

Human Capital and Growth

Building human capital — the sum of a population’s health, skills, knowledge and experience — is increasingly being recognized as the main driver of sustainable and inclusive long-term economic growth. School health and nutrition programs are a critical cog within that process.

In a new report entitled ‘The Human Capital Index 2020: Human Capital in the Time of COVID-19’, the World Bank updated its index (also known as HCI), which is a measure of the human capital that a child born today would expect to accumulate by the time (s)he reaches 18 years of age. The HCI scores are based on indicators that include:

- Child survival (based on the under-5 mortality rate);

- Learning-adjusted school years (a measure that looks at both the number of years and the quality of schooling up to the age of 18);

- Health (an assessment of the health of children under the age of 5, looking specifically at the rate of stunting, as well as adult survival rate that looks at the proportion of 15-year-olds that will survive to the age of 60 or more).

Given these criteria, it is easy to see how any intervention addressing the health, education and know-how of children should be central to human capital development.

School services range from meals and supplements to vaccines and vision screenings.

The HCI score ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 meaning that the benchmark of complete education and full health has been met. With the global average standing at 0.56, Sub-Saharan Africa scores the lowest (0.4), with South Asia following in second place (0.48). North America (Canada and the United States) has the highest score with 0.75, followed by Europe and Central Asia at 0.69 and East Asia and the Pacific at 0.59. Sub-Saharan Africa’s score of 0.4 means that it has only reached 40 per cent of its human capital potential compared to the global average of 56 per cent. In economic terms, this means that, if we were able to fully unleash this currently untapped potential by ensuring the education and health of future generations, the region’s GDP per capita could be 2.5 times what it is today.

Human capital is a fundamental issue not only for the benefits accruing to the individual but also to countries. In higher-income countries, human capital accounts for 70 per cent of total wealth; in contrast, in low-income countries, human capital accounts for only 40 per cent. This highlights the unfortunate predicament that many low-income countries are faced with as their low levels of human capital inhibit their citizens from reaching their potential and countries from unlocking sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

Coronavirus Casts a Shadow Over the Future

The World Bank’s new report goes on to examine the likely impact that COVID-19 has had on human capital. Based on a long-run (2020–2040) simulation, it finds that HCI losses accruing to the current generation of children and adolescents (0–18 years) due to COVID-19 would be 1 per cent on average. In other words, on top of other challenges, COVID-19 could remove a full and critical percentage point from the global HCI for a sizable portion of the future workforce in 2040.

While a 1 per cent drop may seem to be negligible in the long-run, human capital losses due to COVID-19 are likely to be more acute for girls in low-income settings, and children from minority, poor rural or urban backgrounds as well as those with physical and mental disabilities. Many of these children have suffered from learning loss due to school closures and missed out on new learning opportunities. For many, this has increased their risk of dropping out of school, which is particularly high for girls as they are exposed to early marriage, early pregnancy and sexual abuse and exploitation. As schools re-open, school feeding programs don’t only bolster the long-term human capital of a generation, but also serve as an immediate incentive for pupils — especially girls — to return to school.

To ensure pupils continued receiving nutritious food during COVID-related closures, schools around the world provided take-home rations in lieu of school meals.

Faced with these jarring numbers, it’s hard not to be both optimistic at what could be and devastated at what hasn’t so far and the gains lost due to COVID-19. But the math is simple: by promoting access to and continuation in education, school health and nutrition programs support human capital development as they help improve performance on the school years indicator — healthy kids are better able to attend school regularly and, in the presence of improvements in the quality of education, achieve better learning results.

These services also improve the health indicator, both in the short term as they address the current health and nutritional deficits facing children during the pandemic, and in the long term as they increase the years of education of a child, with evidence suggesting that every additional year of education can result in a 2–3 per cent reduction in adult mortality. This can be attributed to children and adolescents having access to information and healthy dietary and behavioral practices in school that can reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases (type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.).

A Clarion Call For Policymakers

No region or country has met its full potential in terms of human capital. Governments, in both high-and low-and-middle income settings, need to continue investing in their people for the foreseeable future — even more so if they want to offset the threat that COVID-19 poses to human capital development.

As the World Bank notes in the HCI report, mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on HCI gains requires policymakers to put in place policies that “expand health service coverage and quality among marginalized communities, boost learning outcomes together with school enrollments, and support vulnerable families with social protection measures.” This is a clear clarion call for policymakers to demonstrate a credible commitment toward human capital development through effective policies and a scale-up of high-impact programs like school health and nutrition.

School health and nutrition programs must be at the heart of the agenda to unlock the potential of future generations.

As many countries begin the process of reopening schools, in the immediate period there is a need to respond to COVID-19’s adverse impact on children by restarting education through interventions that promote re-enrollment and address health and nutritional deficiencies to enable learning. This will help to ensure that no child, regardless of where they live and irrespective of their circumstance, is left behind. Filling classrooms with sick and hungry children that are not ready to learn, does little to advance human capital development — that is why the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) is working with partner governments to help couple the reopening of schools with the continuation of and scale-up of school health and nutrition programs which, in the long-run, will help to boost human capital development.

The world is now at a critical juncture where decisions on the allocation of resources will have a tremendous impact on the recovery and future resilience and potential of countries. If future generations are to reach their full human potential, school health and nutrition programs must be at the heart of the agenda.

Learn more about the U.N. World Food Programme’s work in school health and nutrition and school feeding.

_____________________________________________________

This piece is by Mohamed Abdiweli Ahmed and originally appeared in WFP Insight.